Interfacing with the Player

How good game design can be felt in your hands.

Controllers are an extension of your hands. Similar to the strings in a marionette, they serve as the main interface between you and your character, determining how it acts in a virtual environment. Games have evolved beyond pressing A to jump. Most AAA games require complex control schemes on an already convoluted 16-button controller; all while trying to make it cohesive and natural to the player.

In some ways, designing a good control scheme is an art form. Translating actions that are natural to us into a button layout is no easy feat, and game designers work hard to make it make sense to all types of players, from veterans to newcomers, without favoring one group over the other. This is achieved in two ways: teaching you the mechanics organically through the game and designing a control scheme that feels right in the player’s hands. It’s a level of creativity that mostly goes unnoticed, so it’s worth highlighting games that do it well… and some that don’t.

Learning to walk so you can Run

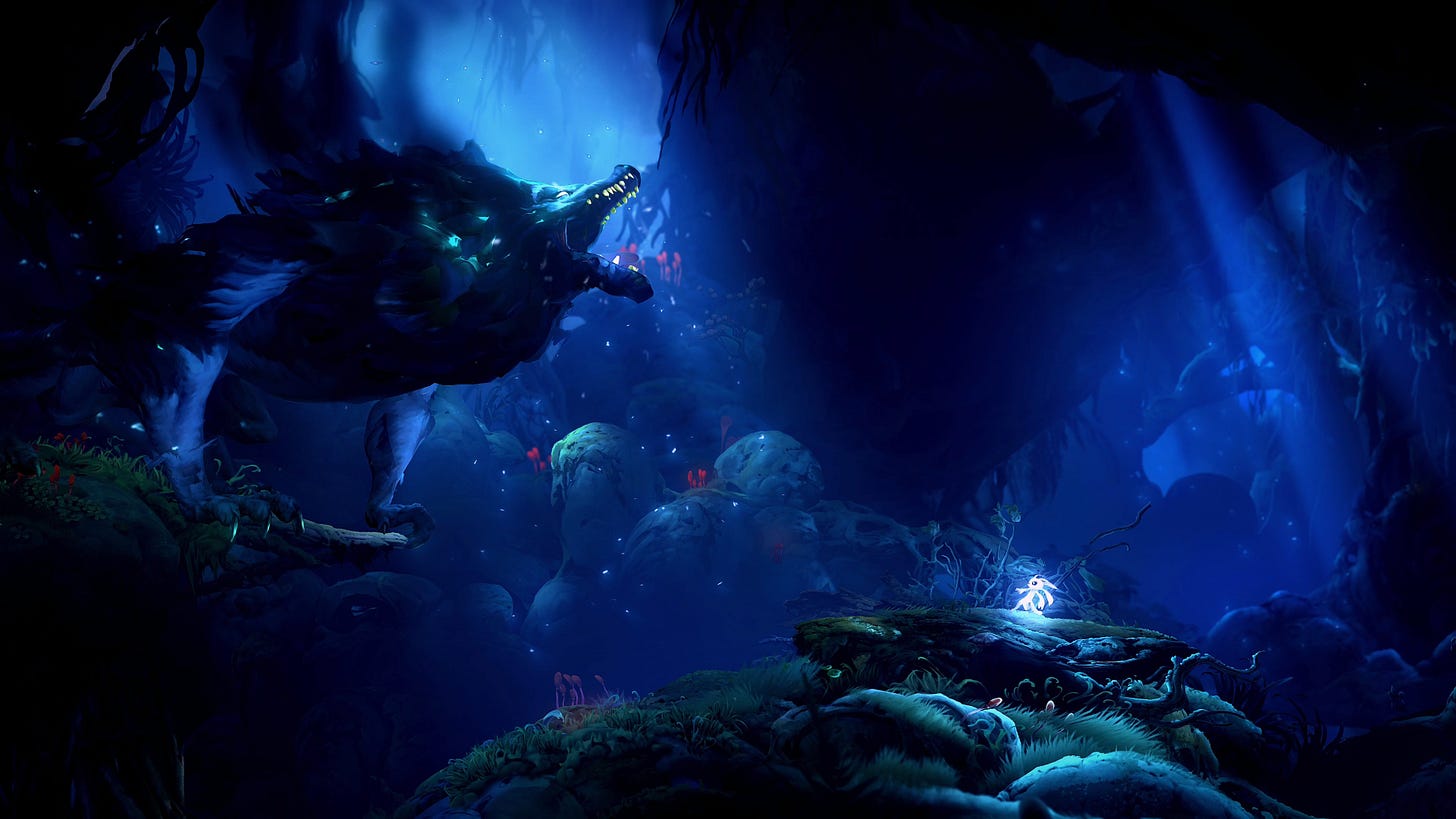

I started thinking about the importance of a good control scheme after playing Ori and the Will of the Wisps, a “Metroidvania” developed by Moon Studios. Games in this genre are characterized by fast movement in a 2D open map, with some areas blocked naturally if you lack a certain ability. For example, all underwater sections of the game are blocked until you learn the dive ability.

The list of abilities you collect grows exponentially throughout the 12-hour adventure; diving, parrying, double jumping and dashing all come in due time, but the game gradually teaches the player, so it doesn’t become overwhelming. As a matter of fact, the player can only leave the area where the ability is obtained by using said ability, attesting you know how it works. The game then gradually puts the player in tougher and tougher situations until the new ability is mastered.

The funny bit is, this experience was a bit different for me. I was more than halfway through the game, learning new abilities and mastering them, when I stopped playing. For a whole year. Life got in the way, so did a new Zelda game, so I left Ori in the back burner for an entire year.

And let me tell you, coming back to it was as easy as pie. After fumbling around with the controls for about 20 minutes, I was back at being an expert. On top of having an incredibly designed learning experience, the control scheme itself is carefully crafted to work hand-in-hand with the beautifully crafted world.

Most movement options in the game are defined by two buttons, RB (Right Bumper) for dashing and LB (Left Bumper) for parrying. Other abilities are tied to the same buttons, but are contextual within the game world, so pressing RB near a patch of dirt, executes the dig action; hitting LB near a lamp, executes the whip action that pulls Ori towards it. The player doesn’t need a separate dig button or whip button because the developers designed the map in a way that doesn’t require you to use abilities tied to the same button at the same time. It’s smart design like this that makes it all feel organic while providing a wide array of abilities that never overlap.

Ori is a shining example of a well implemented learning experience, however, many studios fail to consider the importance of a carefully crafted tutorial. Even beloved indie games, like Stardew Valley, only display a huge screen with the button layout during loading screens, and consider their job done. This results in players having to pause and come back to that screen multiple times to understand how to play, causing a lot of fumbling in the first few hours. Stardew is the type of game where I enjoy learning things on my own, but I am very conscious how difficult it must be for a newcomer in this genre.

Many AAA games have been struggling to find a good balance between having a flashy intro and a useful tutorial for the player. In the Last of Us, the player takes control of a little kid to learn controls, from moving the character, to moving the camera, to focusing and interacting with objects in the environment. This is all done in a safe area, right before the literal apocalypse happens, but even if the stakes are high, the controlled character always feels safe, without detracting from the spectacle of the first hour of the game. The same can be said about Marvel’s Spider-Man, the game manages to create a safe tutorial for the player to experiment, while simultaneously being a fireworks show, that even culminates on a challenging boss fight to test the player.

Another key aspect of teaching the controls is reminding the player. We can’t expect everyone to learn the button mapping just from the tutorial alone, so in most cases, games present a ribbon at the bottom of the screen showing the most relevant buttons at any given time. Games like Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, implement several mechanics for fishing, sailing on a boat, riding a horse, fishing and even drinking; all of these are accompanied by a ribbon showing the control scheme for that particular moment, so the player doesn’t depend on their memory for mechanics that are not that common.

However, my favorite use of reminder mechanics come in the shape of contextual prompts. In games like Life is Strange: True Colors, interactable objects are accompanied by the button required to interact with it. This keeps the interface clean and helps communicate to the player only the buttons necessary at that given moment.

For this next bit I want to start by making very clear that I’ve been loving Baldur’s Gate III so far; it is marvelous to see such an amazing game run before my eyes. Playing it at the same time as Ori, though, made me realize how bad Baldur’s Gate’s control scheme is in the console version. I understand that trying to mimic a complex TTRPG like Dungeons & Dragons will naturally involve a lot of menus and pages upon pages of different actions your character can execute: jumping, running, casting, attacking, throwing, drinking, etc. I get it, it’s too many actions, to little buttons. But I swear every time I play it, I feel like I’m operating an airplane.

I was able to pick up and play Ori after a year of not touching it, and yet I don’t play Baldur’s Gate for 1 (one) week and I feel lost, hitting the wrong buttons, accidentally crouching or turning on torches. The start of the game is rough because everything is available to you from the very beginning, making me feel like a toddler in an engineering class. One of its biggest crimes is having multiple pages of actions which you can open with LB or RB, then allowing you to change the page with the same buttons. The thing is, pressing the LEFT bumper leaves you in the RIGHTMOST page and viceversa. It took me HOURS to get used to this.

Comparing Baldur’s Gate to Ori feels appropriate because it’s missing the two key design choices I praised Ori for: It gives you EVERYTHING from the very beginning, and it teaches you very little on how to exist in this world.

I am happy to report that after playing for over 50 hours of Baldur’s Gate III, I feel more in control now. But it was such a difficult journey to get there. Some games don’t give you dozens of hours to learn and experiment with the controls, such as Ori, which is literally 12-hours long.

Control Scheming

It’s not enough to have a good tutorial, as mentioned in the Ori case, your control scheme must also be easy to understand. A poorly designed button mapping causes frustration, breaking the immersion between the game and player. A good control scheme is characterized by two main factors: Using well-known standards, and associating button inputs with real-life actions.

Standards have evolved throughout generations, especially now that controllers themselves have been taking a similar shape across all available consoles. The options/minus button is almost universally used for opening a map, A/B buttons for selecting and canceling on menus, and the control sticks to move the character and camera around. Keeping these in mind when designing the button mapping will ensure most players learn faster, as they can easily associate one control scheme with another.

It’s important to note that games must still teach you how to play despite utilizing well-known standards. In games like Super Mario Odyssey, the first thing the game tells you is to use the left control stick to move around. Redundant for most, yes, but not for a 6 year old picking a controller for the first time in their life.

I’ll avoid praising games for their use of commonly used standards. Frankly this is the bare minimum. So, let’s focus on the more creative aspect of creating interesting control schemes, and how developers find fun ways to immerse the players even more through the controller.

Shoulder buttons, more specifically Triggers, have been the avenue for creative control scheme design in modern games. While most games use these for menuing, such as the aforementioned Baldur’s Gate III, some games stand out by using Triggers in interesting ways. A common example comes from modern racing games, like Forza and Gran Turismo, which ditched the standard use of face buttons, and replaced them with a Trigger-based layout for accelerating and braking, simulating the pedals of a car.

One of my favorite examples comes in Death Stranding. This is a game about walking. Lots of walking. The main gimmick is that all items your character carries occupy actual space and weight in the world. No more magic backpacks to hold a bazooka. You have to carry items for traversal, such as ropes and ladders, stun guns to defend yourself from attackers, and the actual objective of the quest. It is funny seeing all of these items stack on top of each other as Sam, the main character, starts feeling the weight.

Which brings us back to Triggers. The Left and Right Triggers are an avenue to control Sam’s left and right hand. If you hold the Right Trigger near and object, you start carrying with your right hand, but only as long as you hold the right Trigger. This creative use of Triggers is great because players can very easily associate the clench of your hand with the grip of the character in-game. At times, you can physically feel your hand get tired from holding the button for too long, just like Sam would.

Going for immersion simulating the left and right hands of your character doesn’t always work, though. Many games have opted to use Triggers in action games as the left-hand and right-hand attacks. Examples include modern Assassin’s Creed games, Skyrim and Immortals Fenyx Rising. It works well with guns (they are Triggers after all), but it’s harder to justify losing the snappiness of face buttons in action games with faster gameplay.

A more recent successful example comes in Jusant, from Don’t Nod studios. This game has an emphasis on rock climbing and it mimics standards from the real-life sport, such as having to place pitons and ropes around while you climb. For immersion, this game mimics your left and right hand through the corresponding Triggers. Pressing the Right Trigger near a rock will have your character hold on to it, while you move their left hand to get a grip on the next rock. It works well because, similar to Death Stranding, you simulate the grip of your character with your real grip on the controller.

You can tell Jusant is a 2024 game by the way its controls are designed with all ideas above in mind: The game tutorializes even the most basic character actions, such as movement and jumping, it teaches you all your character’s abilities individually, and then increases the challenge by having you combine abilities to solve environmental puzzles. The control scheme uses standards for movement, contextual buttons when interacting with objects in the environment, and uses a creative button mapping to immerse the player into the rock-climbing experience. It is the epitome of good game design, and I hope more games follow this design principles.

Technology is improving and year over year we see games quality evolve to convey more realism. At the same time, game design is also evolving, and developers keep finding interesting ways of creating control schemes that simplify the interface between the player and the character, as well as creating organic ways for the player to learn them.